13 Dec FROM PILGRIM TO PILGRIMS… Argentine

Accompanying the hopes of migrants and refugees and crying out together with them. A reflection in the light of the experience of St. Ignatius of Loyola.

(First published in Revista Comisión Episcopal Migrantes Argentina)

The entire military career of St. Ignatius of Loyola was cut short with a gunshot wound in the battle

of Pamplona. His entire life was detonated by a shot that, curiously, instead of tossing him into a

void, put him on the road. Ignatius began to go on a pilgrimage and experienced one sole desire: to

follow and serve Jesus, to place himself in his hands forever and to do his will.

That is St. Ignatius, a former solder who, enlightened by his love for Jesus, in the 16 th century, put himself at his faithful service in order to serve those who are always the “last” of history. It is not a pat phrase; it is an image that is necessary to keep in our mind and heart.

Not to renounce a life with dignity

The twenty-first century goes on, and the bullets multiply. Because the migrants and refugees also

have received a wound that has placed them forcibly on the road. All of them are wounded by

political, economic and social systems that detonate their lives, penetrating it with the splinters of

injustice, poverty, persecution, racism, and so many other shameful things that destroy their

aspirations. Above all, it shatters the dream of every human being to live a life with dignity in his or

her country, in his or her birthplace.

That wound hurts multitudes, it forcibly expels thousands of people from their homes and, paradoxically, it becomes a force that, as Ignatius experiences, launches them forward. So, they begin the journey to heal and to find prospects for peace.

These pilgrims are leaving footprints, marks of suffering and hope, and they often enrich our culture with their knowledge and experiences, bound to the nostalgia for those places to which they will not return, at least in the short term — or perhaps never.

They set out also because they seek the will of God that will inevitably involve not renouncing the

possibility of a life with dignity. They do not conform themselves to merely surviving; they have the

certainty that they have been invited to live fully. To maintain that resolve, they stake everything.

The enormous challenge, then ,is to take the journey. They have to travel a road that, delimited by

dislocation and dispossession, obliges them to a constant exercise of letting go, of leaving their

things and their loved ones.

Uniting our lives to theirs

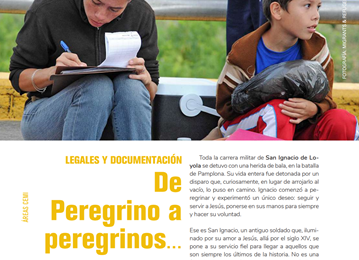

Between Ignatius the Pilgrim and the migrants and refugees, we appear, ordinary people,

anonymous faces that intend to walk with them. We collaborate through a humanitarian

organization, a parish, the Bishops’ Commission for Migrants and Itinerants or an NGO, and we are

associating ourselves with this journey, putting ourselves on the side of the many brothers and

sisters that arrive or only pass through our country in search of that secure land where they can

finally live in peace.

We journey with those who have been forced to leave their place because of fear, of hunger, of persecution, with those who are carrying the weight of the baggage of their history, but always erect and urged on by that dream of achieving the right to a dignified and full life. While we try to accompany them, a redemptive movement envelops us on the journey.

I feel that the journey (my own life) in this key, will never make me like a migrant or a refugee. In

the first place, because I am here where I was born, but above all because my life is full of security.

Nevertheless, what could hinder me has invited me to join this trajectory of my history to theirs.

So, each step I receive as a grace to intimately know the poor, humble Christ who journeys. In them

he teaches me, he guides me, he saves me, he takes me, as he took Ignatius, out of my “comfortable

castle walls” in order to launch me onto the road where Jesus, always compassionate and suffering,

awaits me.

An experience of Saint Ignatius

Life unfolds through those pilgrims, and our role is simply to walk beside them. In order to try to share something of this experience, it helps me to connect with an experience of Ignatius, when he was a pilgrim on the way to Jerusalem. In his autobiography, on describing this route he narrates the following scene. On the way to Jerusalem, from Barcelona to Gaeta, he tells us:

“From those who came onto the boat there were added to the group a mother with her daughter

who was dressed as a boy, and another lad. These followed him, because they were also begging.

Arriving at a farmhouse, they found a large fire and around it many soldiers, who gave them

something to eat and much wine, inviting them, so that it seemed that they intended to teach them a

lesson.

Afterwards they separated them, putting the mother and the daughter upstairs in a room and the

pilgrim and boy in a stable. But at midnight he heard up above that there were loud cries, and

getting up to see what it was, he found the mother and the daughter […] crying that they were

trying to ravish her. This gave him a great impulse, that he began to shout saying; do they have to

endure this? […] the boy had already fled, and all three began to journey thus by night.

(Autobiograpy, [38])

This woman with her little girl could be the thousands of persons – men, women, children, elderly,

today who emigrate, who move through the world, at times in a more orderly and secure way, and

many others exposed to the perils of a precarious itinerary. Also like the woman and child, today

they cry out, do we listen to them?

“Ignatius could hear them… and we? Our society? Our Church? Our government? Do they hear them? Do we hear them?

Do we hear the cry of the Venezuelan engineer, that will be the next young man who serves us in a

bar? The cry of the young Senegalese who spreads his blanket on the sidewalk of the Once Station,

hoping to sell something and send money to his mother? Do we listen to the Haitian that no longer

has a home either here or there, but who is hoping to become a paramedic in the University of

Buenos Aires? The Dominican woman that bears on her body the marks of violence, but who came

with the dream of working as a hairdresser to buy her own home and bring her daughters to a safe

place? Do we listen to the cry of the Russian girl who fell in love with her girlfriend from the

university and fled from xenophobia, persecution and future prison because of her sexual

orientation?

Ignatius listened, but he did not remain quiet: “With this there came to him an impulse so great that

he began to cry out, saying: “Do they have to endure this?”

This reaction of Ignatius, “the cry and the question because of suffering”, are two keys with which I try to reflect upon on my journey with them.

“There came to him an impulse so great that he began to cry out.”

Yes, clearly it is necessary to cry out for them and with them. And this “raising one’s voice” in our

society, begins with recognizing them above all, as persons, without labelling them as foreigners,

through an official seal on the passport of their lives.

They are not only immigrants, nor asylum-seekers; they are not beads, or umbrellas, or afros, or just

Haitians, or Turks, or Arabs or Russians. They are persons, they are brothers and sisters, who hope

for and need (using the words of Pope Francis) to be welcomed, protected, promoted, integrated.

As Christians, our voice should resound next to theirs. Think of how many prejudices, how many

stories and supposed truths we listen to daily. It is important to show that they are not the ones

who are coming to take away our jobs or collapse our hospital system, nor do they occupy our

“place” in the public university. They are not just doctors who arouse distrust when they take care of

us in a hospital emergency room, nor drivers in hired cars whom we doubt know the route; even

less, they are not just delivery boys or girls, or cheap labor that we can exploit.

They are persons who struggle, who seek, who risk, who dream. They are sons, fathers, mothers,

grandmothers, friends, who do not resign themselves, who inspire us with faith in the God who

walks with them.

Yes, it is necessary to cry out for them and with them. Before the organs of government, because

often the immigration policy in turn subjugates the law, that in our country recognizes migration as

a human right. Because raising our voice with them, in this area, is much more than guiding them in

a process or offering a legal orientation. Raising our voice is helping them to stand up and resist the

onslaughts of the immigration bureaucracy, that drowns the immigrant in long months of waiting for

a document that validates his arrival

Yes, it is necessary to cry out for them and with them also before the international organizations,

those that have received the mandate to care for them, but that often prioritize their own standards

of protection above those they protect. It is urgent to pressure them so that rather than just to

speak about migrants and refugees, they dare to speak with them, to look at them face to face, to

listen to their sufferings. It is necessary to remind them to prioritize humanity above meetings in

which they discuss human migration and its consequences, from their secure and untouchable posts,

without entering the journey of the pilgrims.

Also it is necessary to cry out for them and with them to our Church, so that they may feel at home,

so that we may recognize them as “belonging to us”, so that we may offer them a place in the

liturgies, daring to celebrate with them, recognizing the richness of their popular religiosity and their

spirituality, always desiring that our communities may become a space of welcome, and not merely

the place where they receive clothing or some food. It is urgent to raise our voice, to sing their

hope with them!

“Do people have to endure this?”

Immigration must always be a free choice, a respected human right. Never, on the other hand,

should it be a desperate, improvised action or the only way possible to save one’s life, or to save

oneself from starvation, violence, persecution or xenophobia,

In December of last year, Pope Francis, on Lesbos, remembered in the presence of the refugees and

authorities of the island, that “the remote causes should be attacked, not the poor people who pay

the consequences,” and he continued, saying, “To remove the root causes, more is needed than

merely patching up emergency situations. Coordinated actions are needed. Epochal changes have to

be approached with a breadth of vision. There are no easy answers to complex problems.” (Pope

Francis on Lesbos, Dec. 5, 2021)

To question their suffering, to suffer with them, is also an opportunity of grace to open ourselves to

the Risen Jesus and to receive the mission of exercising the office of consoler. And I believe that that

means to accept as “a friend with another friend” those existential questions that rekindle their

present: Who am I? Who is my family? What do I contribute to society? To the world? Whom does

my education serve? Will I be accepted?

Observe how poignant it is to re-create the response to these questions. With unbreakable faith, no

matter the religion that they profess, they continue their journey, valuing the small or great

victories that they achieve: the joy of the first job, moving to a sunnier and more spacious place to

live, the schooling of their children, helping a friend to reach his destination, sending money to their

families.

These are all very necessary paschal joys, yet they do not obliterate the initial question: Is it necessary for them to endure this? They do, without doubt, fortify their determination to continue walking, dreaming, growing more integrated in the locality.

With his cry and his question, Ignatius not only prevented the woman and the child from being ravished; he made a commitment to them. He offered them his unconditional company for the arduous journey. It is, perhaps, on this route of migrants, refugees and pilgrims, in which the cry and the question of Ignatius also resounds within me, where God always confirms to me that this is what the call is about: accompanying hopes.

Constanza Diprimo, aci